This week, THUMP launched a lengthy article titled “I Fooled The World Into Thinking I Was A Successful EDM DJ – For An Art Project.” Inside, the author describes her two-year experience of DJing around the globe, gaining increasing attention – and compensation – from promotors and organizers near and far.

Using her friend’s deep connections and an even deeper sum of money, she was able to book several large gigs immediately. To make sure she stayed successful, she purposely hand-picked the most popular, mainstream EDM tracks of the time to use in her (sometimes prerecorded) sets. By “living the cliché,” the author effectively became a recognizable name in the live show circuit, helped along by the two ghost producers she hired to write tracks for her. Her “art project” – as she refers to it – was ended after two years when she was hired for a real, full-time position in a separate dream job.

The punchline? She never actually enjoyed the mainstream music she became famous for playing.

After reading this piece – and despite enjoying the writing itself – I was left with a serious question: when was she fooling anyone?

When a person claims that they’ve fooled someone, it usually implies some sort of counter-agenda to their actions. By going along with something and making people believe that they’re being genuine, the true intentions and statement of the action is exposed. What this author said she did by “pretending” to become a famous, mainstream EDM DJ was nothing more than literally becoming a famous EDM DJ. There was no pretending other than the irony, I suppose, that her actual music tastes didn’t necessarily align with the music she was playing.

Over the course of two years, she did everything a normal, mainstream, ghost produced, well-funded DJ would actually do to become successful. The only difference was that she secretly didn’t like the music.

In her first three paragraphs, the author describes her disgust with the superficiality and oversaturated spectacle that makes up the backbone of the EDM scene. Having come from an event promotion background, she was already equipped to enter the djing world for herself – something of a rarity among actual, prospective performers. Before proposing the main, overarching questions and themes that she would be attempting to uncover through her project in the fourth paragraph, she directly answers each of them in her introduction.

Q: “Is a DJ nowadays just a puppet who plays music on stage and shoots their euphoric audience in the face with confetti? Does a DJ really still need technical skills, now that even bog standard DJ equipment has an integrated sync-button?”

A: “I was even more disgusted by DJs who contributed to the super-commercialization of that very music. Those who were paid to throw cakes through clubs (and onto wheelchair users) while playing pre-recorded sets.”

Q: “Isn’t large-scale DJing more about a glittering performance than any authentic substance?”

A: “It’s all about mass entertainment, while the content and culture have become completely irrelevant. […] EDM is nothing more than spectacle: boom, boom, and pyrotechnics.”

It would seem that the curiosity to discover the answers to her proposed questions should end here, then. She already has the evidence. The ideas she touches on, while largely true, are ones that have been agreed upon in their validity and fought against for many years by people in the community who actively care for the content and musicianship underneath the layers of mainstream as she claims to be doing.

If the content of the author’s statement about DJ’s consumerist-promoting, art-abandoning tactics was already able to be made in full before even beginning the experiment, and was one that – in all truth – has been spoken and written about to its death over the years, standing as the flagship for the community’s frequently outspoken frustration, why attempt to ironically follow the trend herself?

What is artistic or revolutionary? If no new trails are blazed with it, can an action even be considered a “statement”?

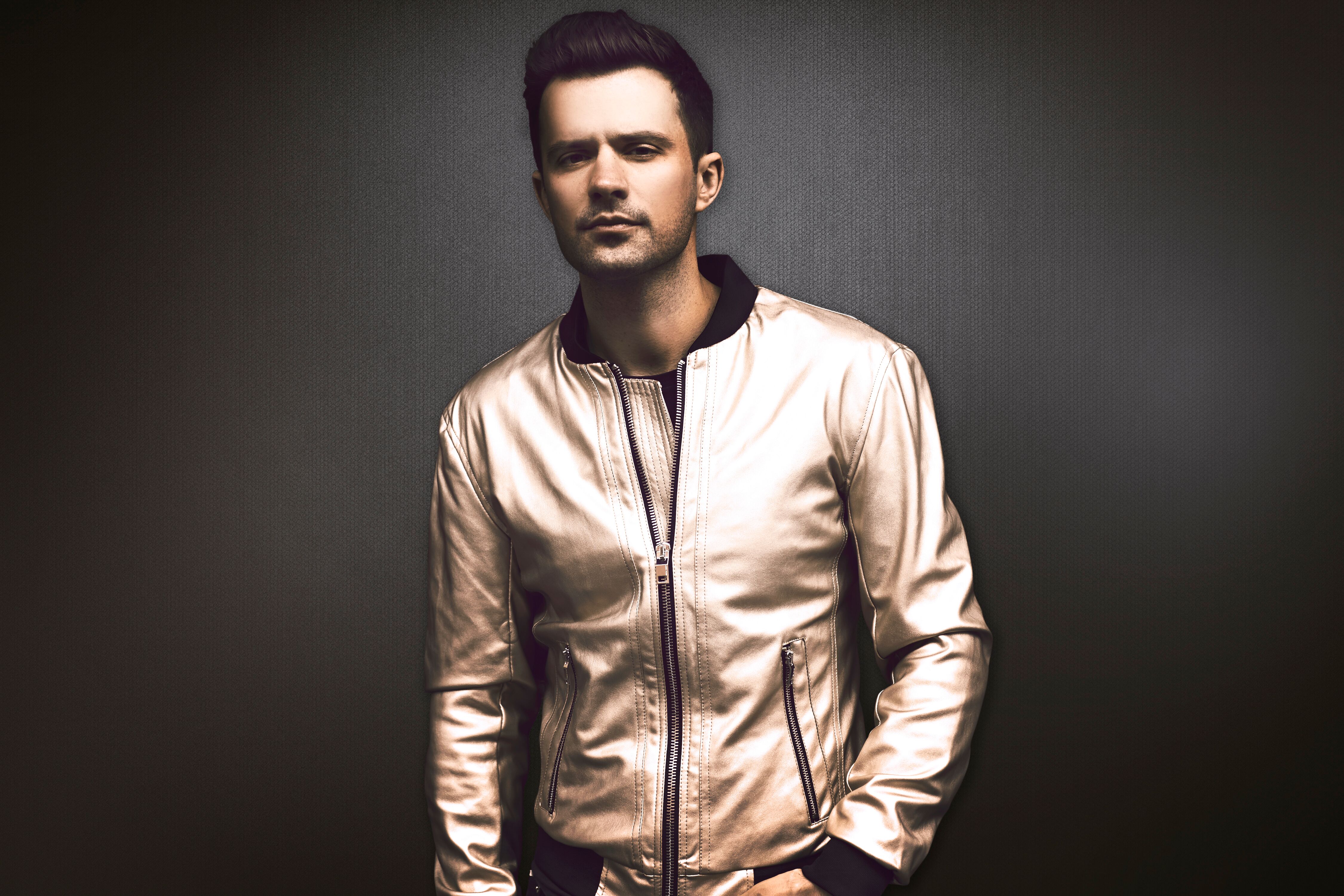

From the outset, the author’s odds were incredibly weighted in her favor. She possessed the resources, connections and money to immediately enter the DJ circuit, and look professional doing so. Her friend Tobias served as an ultimate hookup to gigs, an increasing payroll, travels, hotels, etc. Significant money was spent on logos, professional photo shoots and more to create an image and brand for her DJ persona, and even more – most likely – on hiring the quality level ghost producers she was able to find. According to her, it only took her a few weeks to learn how to DJ convincingly.

All of these things are done by normal DJs with the proper connections and resources in the exact same fashion. Besides the label of “art project,” how can these actions be categorized as different from anyone else who does them? Irony isn’t enough, I believe, to make the imitation of the very lifestyle and actions you despise “art.”

At the end of the piece, the author describes her offering of a full-time position as a journalist – her dream job. Just as any sane person would do, she left the DJing life behind to begin the career she’d always wanted to have.

The “art project” had ended.

While I commend the author for leaving her path toward faux stardom behind, I can’t help but believe that her experiment was a lesson in futility and self-reward. Nothing new was learned, nothing she believed to be wrong was changed, the cultural tendencies she hoped to expose were instead just perpetuated for a laugh, and she was paid to take up someone else’s spot on the rosters the whole time.

I believe this project was an exciting and easy joyride for the author, as she experienced the real perks of being famous and a paid performer. But the only one fooled was herself.

Source: Thump