House. Trance. Techno. Electro. Drum n bass. We’re all familiar with these genre names, and distinctions are important—each style of music derives from a specific background and evolutionary history, and there are many factors that play into what sounds are used, how songs are written, and even what crowds are drawn to shows. But have you heard of minimal tech house with French funk influence? Maybe you have—but chances are you haven’t, and chances are even better that that particular style is too specific to really exist. Genre labels are going the way of metal these days—it has to be death-influenced Nordic symphonic with power vocals and a thrash tempo, rather than just, say, symphonic metal.

Webster defines genre as “a category of artistic, musical, or literary composition characterized by a particular style, form, or content.” EDM genres, then, are completely legitimate from a semantic standpoint; it’s easy and relevant to call two songs trance if they share similar influences and sounds, because they can be characterized as having specific content that is shared between them. But EDM, like every other style of music, has evolved and diversified over time; commonly affected by massive advances in technology as well as changes in the zeitgeist of the community, artificial barriers between EDM styles are starting to break down as the music incorporates new elements and new groups of people become interested in different styles.

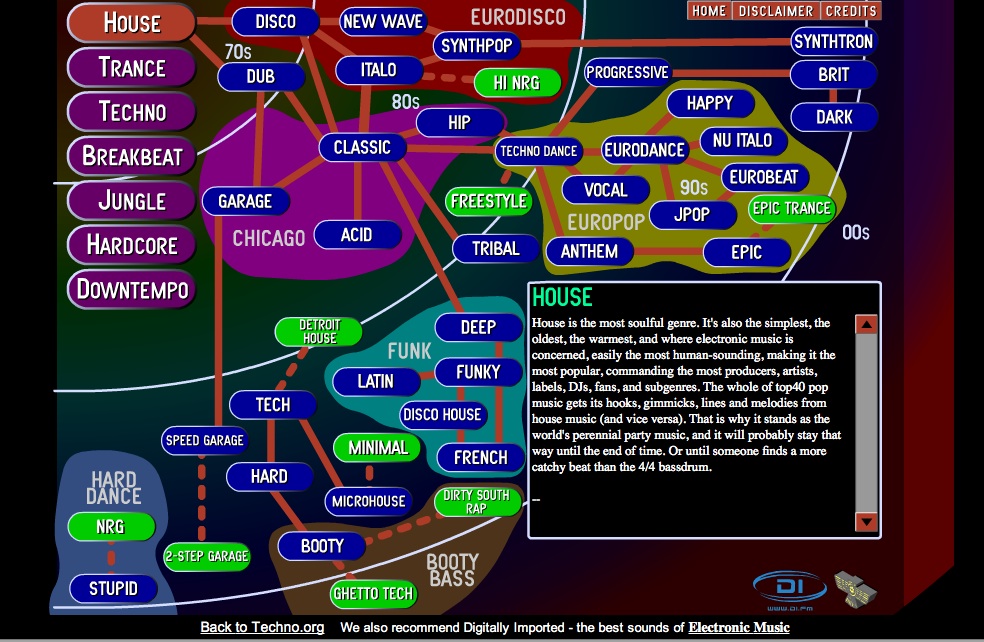

One of my favorite examples of the conception of EDM genre differentiation is Ishkur’s Guide to Electronic Music. An interactive web page with track samples and a complicated network of substyles, Ishkur’s guide can be a bit daunting to navigate at first: pick a parent style on the left, and then work through all of the different substyles to see what sounds like which and why. Perhaps the greatest part of this webpage is so great is because of the categories into which subgenres are placed: not only are they arranged by stylistic origin—for instance, lumping Latin, funky, deep, disco and French house together within a common “funk” bubble—but also geographical origin: house has a Chicago category; techno has a Detroit one; and trance and house both have styles of European origin. This is an important distinction to make when discussing genre categories: sentiments on how music should be composed and arranged differ vastly even in cities as close together as Chicago and Detroit, and as such, it’s relevant to discuss these differences within the context of location, rather than in simple stylistic derivation terms. Working together with the fabulous Digitially Imported Radio—one of my all-time favorite websites—one can read Ishkur’s guide and listen to over 40 different radio stations with various styles of electronic music and really get a sense of why these genre distinctions developed in the first place. (One thing I don’t like about Ishkur’s website, however, is his obvious bias for or against certain styles of music—when creating an informative piece like that, it is important to remain impartial so as not to offend the sensitivities and tastes of the reader.)

It is important to remember, however, that genre label is not an end-all-be-all of what a track sounds or feels like. Every individual has a different conception of how genres should be laid out—let’s call them minimalists and pragmatists. Minimalists are in favor of stripping away subcategories and allowing tracks to remain the simplest versions of their respective parent genres: all house is just house, all techno is just techno, and all trance is just trance. Pragmatists, on the other hand, do the opposite: they create endless substyle categories, based on common elements between specific tracks, in order to come up with a label as meticulously defined possible—so that all house is not just house, but any given house track could be progressive house, disco house, or, yes, minimal tech house with French funk influence.

Is one of these more correct that the other? To some extent, yes—stylistic minimalism pays no heed to the important cultural and philosophical contexts that different types of music derive from, and in this sense, it simply cannot do justice to the full and rich range of subgenres within EDM. But to be endlessly pragmatic about EDM genres is equally incorrect—not only because it’s semantic nonsense that could end up being completely different lingo between two individual fans of EDM, but also because extended derivation of stylistic origin can quickly become overwhelming, and the final label may end up incorporating stylistic or geographical influences that are not present in the track itself. Clearly, the best way to go is to pick a comfortable, middle-of-the-road approach to genre naming—for me, I tend to add, at most, two or three adjectives before a parent genre title. This way, I’m specific enough to distinguish between relevant influencing factors, but not so specific that I get bogged down in the nonsense of repetitive and incorrect labeling.

These walls seem to be continuously breaking down in the modern EDM scene, however. Mirroring the globalization of culture, producers in EDM are more apt than ever to try a new style—I can’t count the number of electro tracks I’ve heard in recent episodes of A State of Trance, some made by classic trance and house legends like Armin van Buuren and Marcus Schossow themselves. Late last year, we saw Kaskade collaborate with Skrillex on Lick It—never in a million years did I think the soulful deep house master would collaborate with the “brostep” progenitor, but he did. The best part? The track actually turned out to be really good.

Not only are people less afraid to experiment with new styles and influences, raves themselves are becoming less and less specialized as time passes. When raves were first emerging as dingy warehouse parties in the late 1980s, it was very uncommon to see more than one style of music being played at any specific party. But now that dance music is exploding into the forefront of the world’s music culture and large production companies are sponsoring huge festivals with hundreds of names, it’s extremely unlikely to hear only one style of music—most big raves these days feature six or seven stages, and large festivals are spread out over the course of several days, even up to a week for the biggest ones. While many parties continue to have a theme of who is playing—generally based on the biggest act booked—almost all of them will have stages where people spin different types of music during the entire festival, so there is diversity for fans to enjoy.

I don’t want to see EDM genre labels go the way of metal—there’s no point for meticulously parsing out each aspect of a given song into discrete influences. While that’s entertaining from a scholarly perspective—and, if you’ve been following my posts, you know that’s interesting to me—it’s simply not practical or feasible. Let’s just all make a resolution to shorten our labels to a reasonable length—and stop the in-fighting about which genre comes from where. After all, if you trace it back far enough, EDM is all EDM—and that is what really matters.

what I think is that as long as the music is a medium to produce art, as long as some of the public receives it as art and it isn’t harmful to society, then why the hell shouldn’t we branch out and create different genres and types and edits and remixes and whatever.

Make and listen to what you want. I don’t think in any facet of society there’s much more to be done, but at the same time what ever is the “next” thing I have a feeling will be mind blowing. Until than I’m loving all the genre blending that’s been going on lately. Maybe see Skrillex Essential Mix for a “bit” of what I mean.

TL’DR: Find something to be excited about if you can’t find it you aren’t looking right.

I wouldn’t call Kaskade a deep house master. He’s more of a big room house maestro.